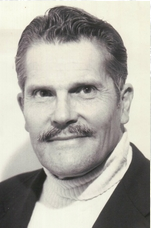

Charles Burwell, a former Darien resident, teacher and selectman who passed away on Feb. 26, 2016 was a 26-year-old naval intelligence officer on June 4, 1944.

His assignment: briefing Generals Dwight Eisenhower and Bernard L. Montgomery on exactly which day the weather would be calm enough for D-Day while the moon was still bright.

Editor’s note: On the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion of Normandy in World War II, Darienite.com is putting the link to this article, originally published on March 1, 2016 back on the Home page and in the June 6 newsletter.

In addition to being on the Darien Board of Selectmen, Burwell was a social studies teacher at Darien High School until his retirement in 1978. He passed away on Feb. 26, 2015 at the age of 98. Here’s his obituary.

Two days later, on the morning of June 6, he was on a ship four miles from Utah Beach, and he went there that afternoon on another assignment to get information.

Burwell used a three-dimensional map of the Normandy beaches to give his presentation, and he still had it in 2003 when he donated it to the Library of Congress.

For that occasion, he was interviewed by library staff; an agency publication, the Library of Congress Information Journal, published an article based on the interview in April 2003. We’re republishing that article and the pictures that went with it, below.

Here’s the article, reprinted here word for word, and with the original pictures (or see the Library of Congress’s own version, here; we’ve changed the paragraph breaks and added some weblinks; the article has Burwell’s age wrong — he was 26):

Planning D-Day

Relief Model of Utah Beach Given to Library

By HELEN W. DALRYMPLE (Photos By PAUL HOGROIAN)

Richard Stephenson, formerly of the Geography and Map Division, and Mike Buscher listen as Charles Burwell (left) describes how he used the map of Utah Beach in briefing troops on D-Day.

On a cold March morning this year [2003], a large, two-part, three-dimensional rubber relief model of Utah Beach in Normandy, France, was spread out on the conference table in the Library’s Geography and Map Division.

Charles Lee Burwell of Millwood, Va., a lively and articulate gentleman with a soft southern accent and a twinkle in his eyes, had come to the Library to donate the map and tell the story of his participation in the D-Day invasion–so that both the map and the role he played on that memorable day could be preserved as part of the Library’s permanent collections.

The map had remained in his possession since June 6, 1944, when, as a young intelligence officer in the U.S. Navy, he used it to brief the commanders of the amphibious assault as well as the troops who were about to go ashore at Utah Beach as part of the D-Day invasion that day.

A raised rubber relief model on a foam backing, the map (each part measuring 47 by 47 inches), shows all of the details of Utah Beach, including tide lines, the slope of the beach, buildings beyond the beach, and the location of “hedgehogs,” which were steel rails welded together in the shape of children’s huge jacks and hidden in the water 30 to 35 feet apart.

The hedgehogs were designed to rip apart the hulls of landing craft that hit them as they came ashore. The map also carries numbers, which corresponded with other more traditional flat maps that were developed for the invasion. According to Burwell, this may have been the first time a rubber relief map like this had been constructed for use in a military amphibious operation.

Jim Flatness and Mike Buscher of the Geography and Map Division unwrap the rubber map of Utah Beach.

Burwell described how the information for the rubber map was obtained, primarily by American pilots flying very low over the area in April and May and taking stereo photographs that were later transferred by photo interpreters into cartographic data for the map.

“The map was made at the last minute, in early June,” Burwell said, so that it would be as up-to-date as possible. The map itself was made at Camp Bradford, Va., he said, and flown over to Plymouth shortly before the invasion began.

Located not far from Norfolk, Camp Bradford was an amphibious training base during World War II; it has since been incorporated into the Naval Amphibious Base, Little Creek, the major operating station for the amphibious forces of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. It is the largest base of its kind in the world.

At the time of the invasion, Burwell was a 27-year-old lieutenant in Naval intelligence, whose role was to help plan for the amphibious assault on the Normandy beaches.

(American troops were responsible for securing the Omaha and Utah beaches, while British and Canadian troops took the more northerly beaches of Sword, Juno and Gold. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was supreme commander of Operation Overlord, code name for the invasion, and the British, under the command of Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, directed the Allies’ Operation Neptune, the naval and amphibious operations that launched and supported the Normandy invasion.)

“I was based in Plymouth, and I got a feeling that [the map] really was helpful,” said Burwell. “The men identified with this map. I think the fact that it was three-dimensional made a lot of difference; it was a technology worth developing.”

The invasion had to take place just before dawn at low tide so that the landing craft could see the hedgehogs and other obstacles in the water, Burwell said. Paratroopers needed the light of a full moon so that they could find their way once they were dropped from the airplanes.

Only three days in June – 5, 6 and 7 – met both of these conditions. He worked with meteorologists, most of them British, (“I was one of the older ones,” he noted) to decide which day the invasion should go. The planned day was June 5, but the weather was dreadful, Burwell said, so it had to be postponed.

He described the briefing on June 4 for Eisenhower, Montgomery and other officers: “[They had] to decide whether to go ahead and sail that night for a landing June 5, or postpone the operation one day until June 6, and whether it would be practicable to postpone it still another day (which it would not be) should the bad weather persist,” he said.

“Here I was in the school auditorium in Plymouth, this stupid, callow youth, scared to death, having to come out on that stage to say what would happen if you postponed [the invasion] one day, two days.”

“The men identified with this map,” Burwell said, as he pointed out all of the features included on the three-dimensional model.

“The men identified with this map,” Burwell said, as he pointed out all of the features included on the three-dimensional model.

Because secrecy for the invasion was paramount, and because most of the men were briefed before boarding their landing craft and other ships on June 4, they could not be allowed to go ashore. They had to endure another 24 hours on board when the commanders decided to postpone the assault for a day.

Early on June 6, Burwell was on the ship USS Bayfield, three or four miles off Utah Beach. “The weather was rough, with choppy tides,” he said. Under cover of predawn darkness, the invasion began, with the minesweepers and the demolition teams leading the way to set off the water mines.

In 15 hours, 23,250 troops and 1,700 vehicles landed on Utah Beach, according to Burwell. By the end of that day, some 200 had lost their lives on that stretch of sand. The toll was much greater at Omaha Beach, where more than 2,000 American troops were killed or wounded.

Burwell described the aftermath: “I came ashore in the afternoon of D-Day; I had to get something from the beach master [troops who acted as traffic cops on the beach during the invasion]. It was just chaos; mostly broken-down jeeps. Most of the wounded had been taken off by then. It was not like Omaha Beach, where there were far more body parts.”

After his role in the Normandy invasion, Burwell participated in the planning for other amphibious assaults–in southern France later that summer, at St. Raphael, near Nice; in the Lingayen Gulf on the island of Luzon in the Philippine Islands (January 1945); and on Okinawa in April 1945.

According to Burwell, the Okinawa invasion was “one hell of an operation,” involving the greatest naval armada ever assembled. American casualties alone during the battle, which lasted until June 21, totaled more than 38,000 wounded and 12,000 killed or missing. “They [the Japanese] used planes loaded with fuel as missiles,” Burwell said. “Long before 9/11.”

After Okinawa, Burwell returned to San Francisco to begin planning for Operation Olympic, the invasion of the Japanese home island of Kyushu slated for November 1945.

“We estimated we would suffer half a million casualties in Operation Olympic,” Burwell said. The invasion never took place, because the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Japan surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945.

Burwell is a descendant of the Robert L. “King” Carter family of Virginia and was born and raised at Carter Hall in Millwood, Va., now the home of Project Hope. He and his wife Natalie have retired to “The Vineyard,” formerly a part of the Carter Hall plantation.

Burwell graduated from Harvard University in 1939 and planned to pursue a master’s degree in history and literature at the Sorbonne in Paris. He was in Paris on Aug. 23, 1939, when the Germans and the Russians signed a non-aggression pact. “I knew it was the beginning of World War II,” he said. War was declared on Sept. 2.

After driving an ambulance in France for the Comite Americain de Secours Civil until March 1940, Burwell sailed for the Far East via the Suez Canal to take a job with the Texas Oil Co. [China] Ltd. in Haiphong, in what was then French Indochina.

Richard Stephenson and Charles Burwell following the presentation of the map.

In the summer of 1941, Burwell returned to the United States and joined the Navy as an ensign in October. When asked why he chose Naval intelligence, Burwell replied, “It struck me that would be an interesting part of the Navy.”

He also observed that his knowledge of French probably had a lot to do with his subsequent assignments. Burwell was discharged on Jan. 1, 1946, as a lieutenant commander with a commendation for his service in the Pacific.

Charles Burwell, 98, was a Darien selectman and a teacher at Darien High School.

His commendation reads, in part: “For excellent service in the line of his profession as Assistant Intelligence Officer on the Staff of the Commander of an Amphibious Group, from November 1944 to May 1945, during the planning and operational phases of the amphibious assaults upon Lingayen Gulf and Luzon, Philippine Islands, and Kerama Retto, Okinawa. … By his leadership and tireless devotion to duty throughout the entire period, he contributed materially to the success of these amphibious assault operations.”

Burwell returned to China with his own import-export business, Burwell, Allen & Co., and later formed another company, Thaibok Fabrics Ltd., in Bangkok, in partnership with Jim Thompson.

He said he was inspired to donate his rubber map model of Utah Beach to the Library of Congress by his friend and neighbor, Richard Stephenson, former cartographic historian in the Geography and Map Division.

Burwell’s discussion of the map model and its use in the assault on Utah Beach was recorded on videotape by Peter Bartis and Jason Lee of the American Folklife Center’s Veterans History Project.

It will be added to the Library’s permanent collections of the stories of veterans of all American wars. For more information on the Veterans History Project, go to www.loc.gov/vets on the Library’s Web site.

The D-Day map Burwell used to brief Eisenhower, Montgomery and other generals.

Pingback: Charles Burwell, 98, Darien Selectman Who Lived History, Then Taught It at DHS | Darienite