Opening on Saturday, Dec. 14, the Bruce Museum’s latest exhibition will feature depictions of sea serpents crushing ships, seven-foot-tall giants, a mummified Porsche, and a menagerie of other oddities sure to pique the interest of any visitor interested in the intersection of art and science.

— an announcement from the Bruce Museum

“Collecting Reimagined: A 2D Curiosity Cabinet” is curated by H.S. Miller of Darien, the museum’s Zvi Grunberg Resident Fellow 2019-20, and will be on view in the museum’s Bantle Lecture Gallery through March 24, 2020.

Below, Miller answers five questions about the exhibition:

1. What’s the difference between a 3D curiosity cabinet and one that’s 2D?

Curiosity cabinets are traditionally thought of as physical spaces filled with objects. They were rooms that European collectors, scientists, and royalty put together for various purposes, ranging from showcasing prized possessions to serving as educational tools.

Photo from the Bruce Museum

H.S. Miller, the 2019-20 Zvi Grunberg resident fellow

At the same time that these collectors in the 16th and 17th centuries are gathering objects for display, they are also describing their collections in catalogues and commissioning artists to create depictions of their cabinets to accompany the text. Some collectors didn’t distinguish between their physical collections and their paper collections — they saw them as part of the same project.

More generally in 16th to 17th century European thought, there was a blurring of physical and paper spaces. The term ‘theatre’ referred to a building, but there was also a rhetorical device where the theatre becomes the place where all knowledge is held. As a result, book titles start to include the term ‘theatre’ because books are places where knowledge is contained.

Creating a cabinet room where the works on display are 2D depictions of typical cabinet objects blurs the already blurry line between physical and paper cabinets. It also further makes the case that cabinets on paper are as much a collection as a room full of natural history specimens.

One more thing: having a paper cabinet creates an incredible opportunity to put on view some of the museum’s ‘hidden treasures,’ if you will. We’ll have on display everything from printed works and photography to medals and scrimshaw, all from the Bruce Museum permanent collection.

2. This exhibition draws on your master’s dissertation; can you tell us more about your academic background and research of curiosity cabinets?

My academic background is in science and art. After graduating from Darien High School, I double-majored in chemistry and religious studies at Bowdoin College in Maine. I then went on to get my master’s in art in the global middle ages at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland through the support of the Keasbey Memorial Foundation.

Photo from the Bruce Museum

Miller with a curiosity cabinet object

The focus of my dissertation was a 1280 CE Arabic manuscript of The Wonders of Creation and the Curiosities of Existence by Zakariya’ al-Qazwini.

Wonders was an extremely popular work during its time. It describes and organizes what can be found in the cosmos and on earth, with a separate section devoted to curiosities. It’s a work that is part natural history encyclopedia before encyclopedias were invented, part rehashing of ancient sources, part travel literature.

The connection with cabinets of curiosities are the parallels I saw between this manuscript and the cabinets that would arise 400 or so years later in Europe. I wanted to show that these two entities, despite being separated by centuries and cultures, were both part of the same historical narrative of collecting.

To help strengthen my thesis that Wonders, which is a manuscript, and curiosity cabinets, which are collections in rooms, were similar projects, I argued that cabinets of curiosities could be found in a paper form. Writing this argument is when I started to think about the idea of a 2D collection.

3. How do you see science and art intersecting in the cabinet of curiosities?

The boundary between the Wunderkammer, the room of wonders, and the Kunstkammer, which is the room of art, was always blurry as an individual’s collection could easily encompass both. In addition, some cabinets were beautifully painted.

More fundamentally — and in my mind, more interestingly — the act of collecting and displaying objects is something that is shared between the sciences and the arts. Scientists collect various specimens, they collect data, and sometimes put their findings on display.

Art collectors acquire various works of art and sometimes put them on display. And I can’t help but wonder to what extent both groups are working toward the same end of gaining knowledge about the world we inhabit.

Also, one of the purposes of the cabinet was to evoke a sense of wonder and marvel in the visitor. And maybe this is just me, but that reaction of awe, joy, and curiosity is the same for me whether I am looking at how incredible the natural world is or at an incredible work of art.

4. As you just mentioned, one of the purposes of the curiosity cabinet is to create a sense of marvel and wonder in the visitor. What aspects of this exhibition evoke those feelings for you?

There are definitely some works in the exhibition that amaze me. We’re displaying a work titled The Giants by a Mexican artist named José Luis Cuevas. It’s a seven-foot-tall print depicting two massive giants, and it’s really hard to look up at it and not have your jaw drop.

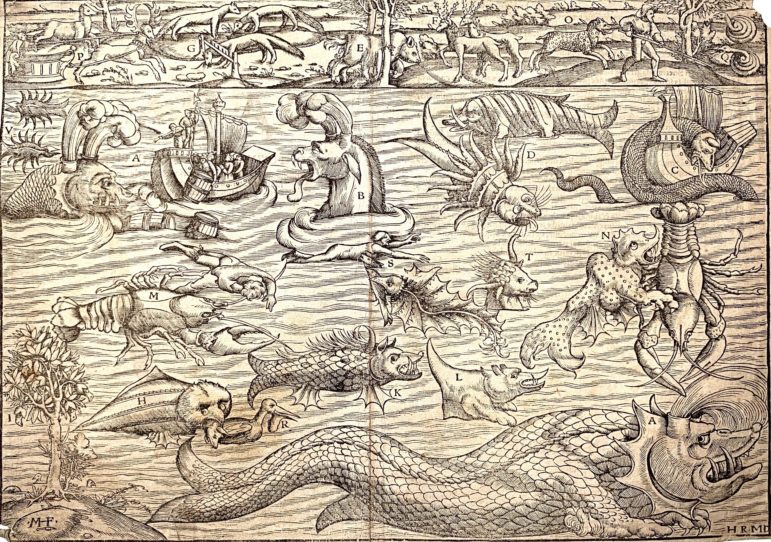

Also, I love, love, love, medieval and early modern monsters, with a particular soft spot for sea monsters. We have on display a 16th century woodcut of sea monsters from Sebastian’s Muenster’s Cosmographia, which was an early modern attempt to describe the world and its contents. I am fascinated by these creatures.

I’m of the opinion that monsters are where you really get to see an artist’s or a culture’s imagination come to life.

Image from the Bruce Museum

“Monstra Marina & Terrestria” by Hans Rudolf Manuel Deutsch

These beasties are cases of scientific observation, ancient sources, and sailor’s tales all mixing together to create just the most marvelous understandings of what was thought to inhabit the sea.

Seriously, what’s better than a rhinolike fish and a lobster dueling each other?

5. Last question: What’s a Zvi Grunberg Resident Fellow?

The Zvi Grunberg fellowship gives a recent master’s graduate or current PhD student the opportunity to gain hands-on experience working at the Bruce Museum. Our job is threefold: We curate our own exhibition (mine is Collecting Reimagined), assist on other exhibitions, and help develop public programming for the Museum.

I’m looking forward to discussing in more detail the stories behind some of the exhibition’s more curious objects in a talk, “Tales from the Cabinet,” on Wednesday, February 12, 2020, 10:30 to 11:30 a.m.

Admission to the museum is free through Jan. 31, 2020, while our main galleries are being renovated. The Permanent Science Gallery will remain open, as will the Bantle Lecture Gallery, Education Workshop, and museum store. Complete calendar listings, including programs related to the exhibition, will be listed on brucemuseum.org, calendar, and reservation pages.

The Bruce Museum is grateful for exhibition support from the Charles M. and Deborah G. Royce Exhibition Fund and the Connecticut Office of the Arts.

About the Bruce Museum

The Bruce Museum is an institution highlighting art and science in more than a dozen changing exhibitions annually. The permanent galleries feature the natural sciences that encompass regional to global perspectives.

Voted the best museum in Fairfield County by area media in recent years, the Bruce plays an integral role in the cultural life of area residents and attracts approximately 70,000 visitors annually, including 24,000 schoolchildren, reaching out to families, seniors, students, and community organizations.

Located in a park just off I-95, Exit 3, at 1 Museum Dr. in Greenwich, the museum is also a five-minute walk from the Metro-North Greenwich Station.

The Bruce Museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; closed Mondays and major holidays. For additional information, call the museum at 203-869-0376.