With the impending opening of the “new” Grand Central Madison rail station serving the Long Island Rail Road, an important milestone in the region’s transportation history will be made. And, in historical perspective, one man’s name comes to mind: Robert Moses.

Photo from Google Life

Robert Moses, October 1952 by Alfred Eisensteadt

Awhile back when I gave a guest lecture to a group of urban planning graduate students at UConn, I made reference in the class to Robert Moses and these planners of our future just gave me a blank stare. “You do know who Robert Moses was, don’t you?” I asked. They did not. I was shocked.

What kind of education were they receiving that they didn’t know the name of the single individual who so changed the NYC area’s transportation landscape in the last century.

From the 1930s to the 1960s, Moses directed the building of 416 miles of parkways (Long Island’s Northern & Southern State and Westchester’s Taconic, to name a few), many bridges (the Triborough, Throgs Neck, Henry Hudson and Verrazano-Narrows, as well as the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel) and designed Jones Beach and the New York State Parks System. He orchestrated two World’s Fairs (1939 and 1964) and helped bring the U.N.’s headquarters to NYC.

Robert Moses’ grip on power came from appointment to 12 different job titles, though he was never elected to public office. Despite all this work he did nothing for mass transit. He loved cars but didn’t really care for people who did not own them.

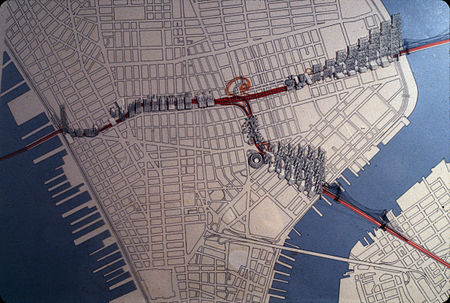

Photo from the Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection

Moses with a model of the proposed Battery Bridge

In locations where others had envisioned expanding the city’s subway lines, he built roads, displacing thousands of residents. Robert Caro, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Moses, “The Power Broker,” even called Moses a racist, because he built motorways for the middle class while discouraging the car-less (people of color) from visiting Jones Beach by making the parkway bridges too low for buses.

He opposed blacks moving into Stuyvesant Town, a Manhattan development on the Lower East side for veterans. City swimming pools in black neighborhoods were kept cold to discourage blacks from using them.

Moses’ dénouement came when he tried to build the elevated, 10-lane Lower Manhattan Expressway which would have connected the Holland Tunnel to the Manhattan Bridge straight through Greenwich Village and Little Italy, evicting 2,000 families and 800-plus businesses. “The Master Builder” called it “slum clearance,” but residents like Jane Jacobs (author of the “Death and Life of Great American Cities”) fought back and the city’s artistic heart was saved.

Lower Manhattan Expressway

Robert Moses was not an evil man but a product of his time. Today, many hail his accomplishments and think we need a benevolent despot like him to get things done in transportation and urban planning, even if a few people get hurt along the way. It’s all for the greater good, Moses once said:

“I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs.”

History will judge Moses — those he helped and those he hurt. Love the omelet, forget about the eggs? But for graduate students at UConn to be unaware of this man, what he built and how, worries me greatly. To paraphrase George Santayana: Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

____________________

Contributed photo

Jim Cameron

Jim Cameron has been a Darien resident for more than 25 years. He is the founder of the Commuter Action Group, sits on the Merritt Parkway Conservancy board and also serves on the Darien RTM and as program director for Darien TV79. You can reach him at CommuterActionGroup@gmail.com.